I have always wanted to live with a work of neon art. For years, I admired the glowing sculptures by classic avant-garde pioneers of the medium, such as Chryssa, Bruce Nauman, Joseph Kosuth, and Keith Sonnier, as well as those by younger practitioners of neon, including Jason Rhoades, Tracey Emin and Alex da Corte. Neon art has a strong relationship to the ubiquitous commercial signage that I grew up with in suburban USA in the 1960s and 1970s. My aunt owned a tavern, and when I visited off hours, the flickering beer signs in the windows would mesmerize me for long periods of time. With their emphatic use of language, combined with the unmitigated sensuous allure of pulsating light, the signs appealed to me on a number of levels.

By the early 1970s, advertisers largely abandoned neon in favor of backlit plastic signs. Fortunately, a number of contemporary artists at that moment rescued neon from oblivion and imbued it with new life as a fine art medium rather than a mere marketing tool. Suddenly, as neon historian Christoph Ribbat notes in his book Flickering Light: A History of Neon, “The handcrafted technique of neon lighting was also rediscovered, and now—this is the paradox—it was treated with great respect and care. . . For many artists, the glow and flicker of the tube became an emblem of the true city, of craft and of visible and tangible materiality.” 1 The art world recognized neon as a uniquely expressive postwar medium—on par with the contemporaneous development of acrylic paints, video and other experimental mediums—offering exciting possibilities for artists of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.

Innerspace, Annesta Le solo exhibition at Yi Gallery, 2020, installation view. Photo by Christian Nguyen.

Innerspace, Annesta Le solo exhibition at Yi Gallery, 2020, installation view. Photo by Christian Nguyen.

By the time I got to the building exit, I abruptly realized, as if recalling a dream I had had, that this was the neon piece that I was meant to live with... I believe that sometimes it helps an independent art writer or critic, as I am today, to live with a work of art in order to more fully understand the artist’s aim and vision. Art as subtle and arresting as Le’s takes a considerable amount of time to fully reveal itself—days, weeks, perhaps years.

One day in 2016, while visiting galleries in the trendy Bushwick section of Brooklyn, New York, I happened upon a group show with a diverse array of works by young artists, of varying materials and quality. Quietly illuminating a side room, a glowing blue neon cipher, hanging in the center of one wall, dominated the space. With its softly radiant cobalt hue, the work beckoned me into the room. Its peculiarly shaped glass tube resembled a cursive lowercase “r,” though upside-down and slanted to one side—unlike any neon work I had ever seen. Two long black electrical wires, curving to the floor, were clearly an integral part of the elegant composition. A glimpse of the gallery checklist revealed that the piece, titled hookup (2015), was by Annesta Le, an artist whose work was new to me.

The shape of hookup suggested an allusive glyph or a letter in a foreign alphabet. Its title, however, hinted at an interpersonal relationship, indicative of some physiological element with a psychological dimension. I left the gallery and headed down the hallway, thinking about the image-text conundrum that the Annesta Le work presented to me, not to mention its indelible, radiant beauty. By the time I got to the building exit, I abruptly realized, as if recalling a dream I had had, that this was the neon piece that I was meant to live with. I retraced my steps, reentered the gallery, and arranged with the gallerist to acquire the work. I believe that sometimes it helps an independent art writer or critic, as I am today, to live with a work of art in order to more fully understand the artist’s aim and vision. Art as subtle and arresting as Le’s takes a considerable amount of time to fully reveal itself—days, weeks, perhaps years.

The cool and gentle, meditative atmosphere that hookup generates as it illuminates the hallway outside my bedroom, has enthralled me every day since. It has also proven to be key in appreciating the unique qualities of Le’s art, and her artistic vision, which I have gotten to know better over the past four years or so. With a background in computer science, and self-taught as an artist, Le creates works that are wholly intuitive, idiosyncratic and personal, while they encompass a significant intellectual breadth. She is also well attuned to developments in contemporary art, as her work allies itself with artistic forebears like Keith Sonnier and Tracey Emin.

Le’s installations often share post-Minimalist nuances as well as the immersive drama of certain neon works by Sonnier, who aimed in his art for a sensory experience. “It’s much more about the psychological aspect,” Sonnier has remarked, “It’s the psychological drama of being in the space. It’s about a mental exercise. And that’s why I go back to the five senses: mine is about a sensual response.” 2 In her neon works, with their textually articulated range of emotions, Emin conveys a personal journey of perseverance, of lost love, and the self-empowerment that enables her to thrive in a male-dominated society.

Le’s art is also part of a personal journey of self-discovery and awareness. She is the daughter of Vietnamese immigrants to the U.S.—boat people, in fact.3 Her mother gave birth to Annesta soon after the family arrived in the U.S., in 1980. Her upbringing was tumultuous. She had to overcome formidable obstacles—forces of external prejudice as well as internal self-doubt—in order to arrive at a state of self-possession and self-awareness that would allow her to become an artist. Also pivotal in her life’s journey was a visit to an Ayahuasca retreat in Brazil, encouraged by her husband, which proved to be a revelatory experience. Working with the shamans there, she found her calling—and her confidence—to establish herself as an artist. Soon after returning to the U.S., she set up her first studio in New York City, a modest space, where she began to paint and draw.

Innerspace, Annesta Le solo exhibition at Yi Gallery, 2020, installation view. Photo by Christian Nguyen.

In the neon workshop, her body movements determine the forms...Recent works by Le refer to the dynamics of anthropometry, as well as to recent dramatic changes in her own body.

The writings of Carl Jung, Jungian psychoanalysis, and especially his concepts of dream analysis, helped her deal with artistic challenges early on, and to develop her own methodology in art-making. The process of creating works in neon soon attracted her, and her approach to the medium was completely intuitive. The alchemy of the practice, with its illusive materials combined with the sheer physicality of production—heating and bending the glass tubes into unique shapes—matched her sensibilities. In the neon workshop, her body movements determine the forms. Though wholly abstract and often resembling an asemic script or written language, the resultant shapes allude most directly to the human body, its limbs, protuberances, and imperfections, plus the sensuality of the human form in general. Recent works by Le refer to the dynamics of anthropometry, as well as to recent dramatic changes in her own body.

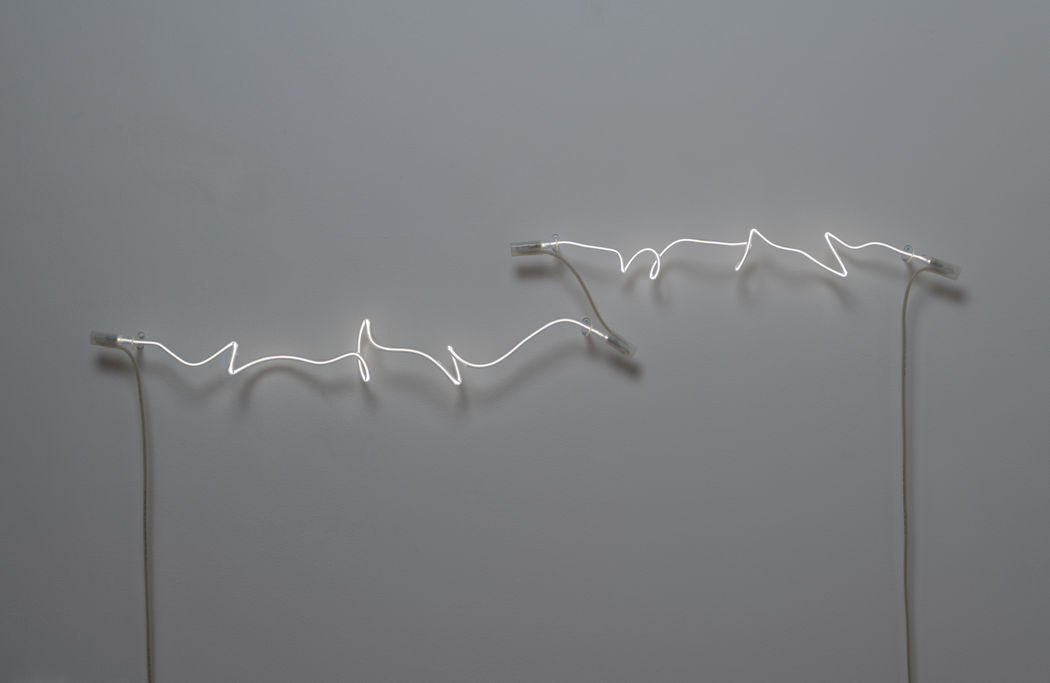

Revealed No.1, Revealed No.2, installation view. Photo by Christian Nguyen.

Le’s efforts of the past several years have culminated in Inner Space, the current exhibition at Yi Gallery. The spare monochrome white palette she used for the exhibition, clear glass tubes and the rare noble gas, Krypton—glowing softly and ethereally white—appropriately signifies purity, and suggests an origin story. Here, two sculptural elements suspended from the ceiling illuminate the gallery space. Titled Revealed No.1(2020) and Revealed No.2 (2020), they were created in the same workshop session. Sensuously articulated forms, like a distinctive asemic calligraphy or undulating white ribbons, approximately five-and-a-half feet long and eight inches high, meander horizontally overhead, like a celestial vision—an imaginative Aurora Borealis of the mind, perhaps.

Innerspace, Annesta Le solo exhibition at Yi Gallery, 2020, installation view. Photo by Christian Nguyen.

Hung along the wall are two pieces from the “Exposed Form” series, mounted on 24-by-24 inch fine-grain wood panels. In this series, gracefully articulated lines describe simple abstract shapes made of thin glass tubes glowing with cool, white-blue Krypton. Each of these brilliant, quasi-Minimalist compositions recalls a particularly sumptuous oil painting, such as a classic work by Robert Ryman, for instance. Le’s vision for this series, however, is somewhat more pictorial. Exposed Form No. 3, for example, a spare composition, features a single, sensuously curving line spanning the panel; it suggests in some way a snowbound wintry mountaintop. The interlocking rounded shapes in Exposed Form No. 4 appear rather figurative, like the outlines of two human heads. These forms relate most directly to Le’s figurative marker drawings—two-dimensional works that she produces in tandem with her neon sculptures and abstract constructions. The drawings, showing featureless faces and schematic outlines of breasts or torsos, are archetypal rather than descriptive. In some sense they are emblematic of Le’s endeavor as a whole. Her emotionally wrought and personal objects and images consistently embody coolly divergent and universal themes. ■

Essay © David Ebony 2020

1. Christoph Ribbat, Flickering Light: A History of Neon, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 2013, p. 132.

2. Keith Sonnier, Files, Interview with Barbara Bertozzi Castelli, Castelli Gallery, New York, 2011, p. 16.

3. “Boat people” refers to the thousands of Vietnamese who fled their country by sea after the collapse of the South Vietnamese government, beginning in 1975, and continuing through the 1980s.

Add a comment